Thérèse Blanchard sits eyes closed with her face turned to reveal her profile. Her fingers interlaced rest on her head. She is beautiful, she is plain, a child, a young woman, both.

She is our finest achievement, our worst endeavours, our aching, our wistful memory and our hypocrisy. She is the painted embodiment of the idea that we don’t see the world as it is but as we are.

Balthus painted Thérèse 10 times over the course of about three years as she grew into pubescence. In the painting titled Thérèse Dreaming, Balthus shows us to ourselves with his young model’s pose asking more difficult questions than I had expected coming to his work for the first time. Whatever our reactions, she doesn’t look back and the length of our gaze and our focus is left to us and however we come to it; a kind of – your problem, you deal with it.

Thérèse dreaming, 1938 - Balthus

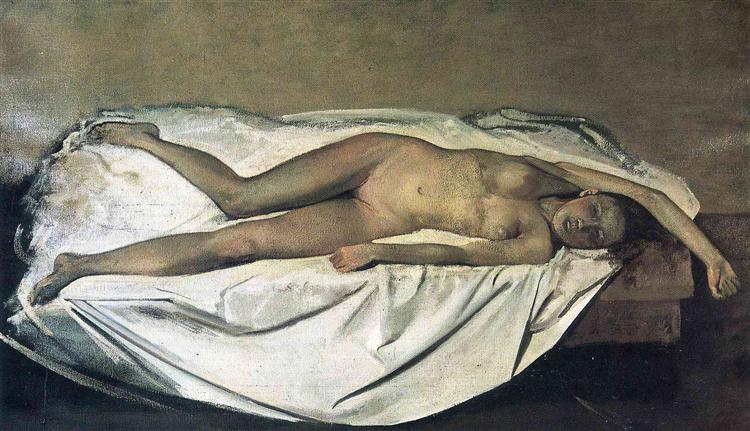

Thérèse, 1938 - Balthus

In another work Thérèse sits as a Michael Angelo statue, her youth undermining the posture. This time her eyes are open but as the pose prods, her gaze beyond us restrains the voyuer. On the cusp of young womanhood, precariously balanced with a foot in each world she is unaware of the complexity of the power she weilds.

She is also being directed for us by an artist who does have some understanding of her power and it is he who draws us into this three way affair. Her look is of effected knowing and with her skirt slid down the exposed thigh of her crossed leg it isn’t how we should see her and yet she’s right before us. Coquettishness and sexuality superimposed on a 12 or 13 year old. A look of knowing that has been learnt but not experienced and has nowhere to go; a thin veneer of invitation failing to hide the girl beneath.

Thérèse is our narcissism, a child to protect, to nurture, the damage we can’t undo – a memory of our youth which haunts us and taunts us.

A little over 80 years on and padded bikinis are sold to girls of a similar age to Thérèse and images commodifying youth fill advertising hoardings. Imagination has become a lazy couch potato accustomed to a constant stream of anything and everything. What once provoked us now strokes us and deals in happy endings not thought. Sex and youth accompany us wherever we wander, reminding us our day is done or soon will be. But never mind, here’s someone else’s as you lick your wounds.

For all the cures and antidotes on sale, time is as relentless as it is unforgiving. Eventually we are left with a ghoul staring back at us from the mirror as we fight the futile fight of ages. It’s twighlight before you know it but it ain’t dark yet. It’s a turning tide and however many King Canutes line the shore, it always comes in.

The Balthus exhibition at Madrid’s Thyssen gallery was my first exposure to the artist and my reactions were unencumbered by prior knowledge of him. As neither artist nor critic my feelings came viscerally and only later was I aware of how much scandal lay in the wake of Balthasar Klossowski de Rola and his use of pubescent girls in his art. (For a more comprehensive view of Balthus’ life and work here is worth a look among other sites.)

The campaign and petition in New York to have some pieces removed from a recent exhibition smacks of the selectively puritanical foothills of moral censorship. A clumsy attempt at a blasphemy law where perceived offence is enough to silence everyone but the self proclaimed pious.

Is there not enough to fuel outrage today with child brides, child prostitution, child labour, child soldiers and child rape by the clergy barely scratching the surface of the horrors dealt to children. How much of the past would be left to us were the impulse to sanitise it given free rein? What would we learn from? Who could claim the sanctity to remove the stain of our deeds and who would judge what was sinful? Not those who have taken it upon themselves to do so up to now, surely that much is clear.

Real life for Thérèse Blanchard was short and in 1950 she died at only 25 years of age. Retrospectively we are seeing a girl about halfway through her life; her middle years brought forward so young as we move past, tutting, sighing and judging from perspectives that will change as we move to vantage points as yet unimagined. Thérèse’s few years as Balthus’ muse are locked into oil on canvas where she remains forever young. However, she did have another life beyond us when she got up, went out of the studio and lived out the brief time she had – as a young woman away from our gaze if not our conjecture.

With both artist and subject now gone, the only remaining part of the three way affair is the viewer/voyuer and shutting it down because we’re uncomfortable, well that’s on us.

Whatever brought Thérèse’s life to an end is unknown to me and has no bearing on the artwork. What does matter is that we look at her and deal with ourselves and what her images ask us. Hiding her away won’t alter who we are.

Well said! The censorship of this is beyond hypocritical.